In 1951, Alan Turing predicted machines might one day surpass human intelligence and ‘take control.’ He created a test to alert us when we were getting close. But seventy years of science fiction later, the real threat feels like just another movie plot.

THIS EPISODE FEATURES:

Connor Leahy, Max Tegmark, Robin Hanson, Karen Hao, Nick Bostrom, Sam Harris, and Justin Murphy

Available to listen on Apple and Spotify.

Here’s the transcript!

Gregory Warner:

I’m Gregory Warner, and this is The Last Invention.

FOX Business:

On November 30th, 2022. The world as we know it changed forever with the introduction of ChatGPT.

News Coverage:

The robots are taking over the internet, going crazy over new artificial intelligence called chat GPT.

Gregory Warner:

So much of this moment that we’re in in the AI revolution. So much of this debate that we’re having about what we should do next was triggered by the arrival of ChatGPT.

News Coverage:

The next generation of artificial intelligence is here.

News Coverage:

It took Netflix more than three years to reach 1 million users.

News Coverage:

But it took ChatGPT just five days. The program can write really complex essays, books, news articles, and even computer code.

Gregory Warner:

And whether you’re a ChatGPT fan or not, that single AI chat bot and the models it followed. They supercharged an industry, shifted our relationship to AI, and fueled this debate about our future with intelligent machines. And that moment, that meteoric impact on our collective conversation that wasn’t just predicted. That moment was forged over 70 years ago in the middle of a war.

Andy Mills:

All right. Greg, so in a lot of ways, what we think of today as artificial intelligence, it comes out of the Second World War.

Gregory Warner:

Again, reporter Andy Mills

Andy Mills:

And actually not just the war, but one battle in that.

Archival Tape:

The battle of the Atlantic continues as our convoys pass to and fro. U-boats lurk in the vast waters, preparing to cut our lifelines at every opportunity.

Andy Mills:

All right. So for context, it’s 1940, and the Germans have all but cut off the supply lines between the U.S. and Great Britain in the Atlantic Ocean, thanks in part to this technological edge that their navy has in the form of U-boats.

Archival Tape:

Hitler has lost the whole weight of his U-boat force against our lifeline in the Atlantic.

Andy Mills:

And it became clear that if they couldn’t stop these U-boats, they might lose the war.

Archival Tape:

The battle of the Atlantic holds first place in the thoughts of those upon whom rests the responsibility for procuring the victory.

Andy Mills:

One great hope that they had to reverse Germany’s dominance in the Atlantic was to crack their Enigma code that they used to communicate with these U-boats. But the trouble was, month after month, as hundreds and thousands of soldiers died and ships sank, nobody could crack it, right?

Gregory Warner:

And just to clarify it. So codebreaking at that point in history was still a very human endeavor.

Andy Mills:

Yes. At this point, it is very common for pretty much every military across the world to have a team of codebreakers that they work with, where they try and intercept and decode the communications of their enemies.

Gregory Warner:

Right.

Andy Mills:

But none of those teams in the Allied forces were able to crack this code. And so back in England, a team was assembled of a somewhat unlikely group of people.

Andy Mills:

You had mathematicians, academics, and even some chess masters.

Gregory Warner:

And these were folks who were not in the military. The military was trying to recruit beyond their ranks.

Andy Mills:

Yes, they were recruited out of the classrooms, recruited out of their research labs, and essentially given Enigma. And the government said, look, we need help. Is there anything you could do? And eventually, after a lot of trial and error, they ended up constructing this electromechanical, essentially calculator that could sift through millions and millions of possible configurations of this code, something that would have taken a human group of codebreakers weeks and weeks in just hours. And lo and behold.

Archival Tape:

German submarines have been surrendering all over the place in fairly satisfactory numbers.

Andy Mills:

They crack Enigma. It opens up the Atlantic. And this is how you get you know, events like D-Day. The Americans could now travel the Atlantic to Europe. And many people think that this is one of the key factors that leads to the Allied victory over the Nazis.

Archival Tape:

Time and time again, the very issue of the war depended on the breaking of the U-boat. And now, as some of the last U-boats came in from sea, no one forgot the lives given and the battles fought against the very grave menace they...

Andy Mills:

And the main guy behind that codebreaking team, his name was Alan Turing. And according to the people that I interviewed right there in the middle of the war, looking at this big electromechanical contraption that he had helped make, he was already envision ING the day when that machine would be able to think for itself. If we were trying to tell the story of where AI is at right now and where it might be headed next. Where does that begin?

Connor Leahy:

Alan Turing.

Max Tegmark:

Alan Turing.

Liv Boeree:

Alan Turing, obviously one of the godfathers of computer science

Keach Hagey:

And was the father of AI.

Gregory Warner:

So from almost day one, Turing saw computers not just as tools that could break codes, but as machines that could think at the highest level.

Andy Mills:

Yes. And from the very beginning of this field of computer science, he inspired this goal to make what today we call AGI.

Connor Leahy:

It is the genesis, the Earth like philosopher’s stone of the field of computer science.

Kevin Roose:

Basically, this is the holy grail of the last 75 years of computer science.

Andy Mills:

And even more dramatically than that. He believed that ultimately the machines would think even better than humans, and that when that happened, they would be able to take control.

Connor Leahy:

He talks about how surely one day, you know, there will be machines that can converse with each other, improve upon their thing, do anything that human can do, and they will surely leave humanity behind.

Max Tegmark:

The idea that this is possible has been around for a very long time. Alan Turing in 1951 said that the default outcome is that the machines that are going to take control.

Andy Mills:

This is something that I talked to Max Tegmark about. He teaches machine learning at MIT and is a very influential voice in the AI debate we’re having today.

Max Tegmark:

Because he didn’t think of AI as just another technology like the steam engine, and thought about it as a new species. But Turing was pretty chill about it and said, you know, don’t worry about it. It’s far away. He was right. It was far away from 1951. And he said, But I’ll give you a test. So you know, when you’re close, I’ll give you a canary in the coal mine. It’s called the Turing test.

Andy Mills:

And Max says that this is one of the reasons that he created what’s called the Turing test. You know, the train test, right?

Gregory Warner:

I think the Turing test is where you’re chatting with a possibly a machine, possibly a human, something on the other side of the screen. And the goal of the test is, can the machine fool you into thinking that you’re actually chatting with a human?

Andy Mills:

Yes. That, in short, is the Turing test. Can you be in conversation with the machine and not know the difference between it and a human being? And Tegmark, he was saying that this was not a benign test. This wasn’t even necessarily just a test of the machine, but it was a way to send a signal to people in the future to say that once you’ve crossed this threshold.

Max Tegmark:

When machines can master language and knowledge at the level of humans, then you’re close.

Andy Mills:

It was like a warning shot to the future to tell them there’s no going back, because soon it will be outside of our control.

Gregory Warner:

And did Turing see this future of machines taking control as something good or something he was warning us about?

Andy Mills:

Well, that question is very much up for debate right now. A lot of the people who are worried about this moment, we’re in with artificial intelligence now, they look at this one line where he said, once the machine thinking method has started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers at some stage, therefore, we should have to expect the machines to take control. And they say, obviously that sounds very foreboding. He was warning us that this was going to be dangerous. But in most of his lectures he’s far more matter of fact. And a lot of people point out that Turing himself, he wasn’t a moralist. He was a contrarian. And he often went as far as to say that when this happened, the machines would, quote unquote, deserve our respect. And so a lot of the people that I spoke to said that trying to take Turing or the Turing test and to turn it into something dumber or something accelerate is missing the point.

Robin Hanson:

I actually think the difference between the optimists and the pessimists can be overstated. I think the fundamental difference has always more fundamentally been between people who thought this was a real possibility to take seriously, and the people who didn’t. And I think the main thrust of the argument was to say, look people take this seriously. This is a thing.

Andy Mills:

This is something that I was talking about with Robin Hanson. He is an economist. But he also for many years was an AI researcher.

Robin Hanson:

It’s a rhetorical device to try to get people to take a space of possibility seriously. There’s certainly in academia there’s just a long tradition, quite reasonable saying, until you can even tell me what your words mean. I’m not really interested in taking your conversation seriously. Right. So Turing was primarily trying to just make sure we could talk about an AI and have that be somewhat precisely defined, so that you wouldn’t dismiss the idea by just saying that’s too vague.

Gregory Warner:

Alright, it sounds like so Turing didn’t just give us a test of how we’d know the I could think, but actually gave us some kind of practical, concrete way of saying, okay, no, this is artificial intelligence when it can talk back to us and convince us it’s human.

Andy Mills:

See, it’s more complicated than that. That’s what I thought the Turing test was for a long time, that once it can do this, it is now officially an AI. But he actually didn’t think that it was going to suddenly be super useful in this moment. It wasn’t that now you are in the presence of a true thinking machine, and it’s tomorrow going to start taking over. What he was doing was more nuanced. He was giving the field of computer science a goal that they could shoot for. Right. He was saying, this is something you could technically go out and build. But in this deeper sense, he was producing this story that the broader public could understand. And making this prediction that once this moment happened, once a machine could so thoroughly mimic how an intelligent person communicates that we would treat it differently, that we would imbue it with something profound and utterly transformative.

Gregory Warner:

So it’s not just a test of the machines and how far it’s come, but it would change our relationship to the machine?

Andy Mills:

Right. In some ways, it’s just as much a test about us as it is a test about the machine.

Gregory Warner:

So what happens to that dream of Turing’s? Well.

Andy Mills:

Sadly, Turing dies in 1954. It’s a terrible story. He was prosecuted by his own government for being gay.

Gregory Warner:

Because homosexuality was illegal in England at that time.

Andy Mills:

Yes. He was sentenced to what they called chemical castration. And allegedly, he committed suicide. But Turing’s dream doesn’t die with him. It gets picked up by a group of scientists in the U.S., many of whom actually knew Turing personally. A lot of them had corresponded with him, and they raised money for a ten week summer program at Dartmouth, where the idea was to come together, create a prototype of a true thinking machine, and to turn the entire pursuit into a proper field of study.

Karen Hao:

So the AI discipline is founded in the summer of 1956.

Andy Mills:

This is a story that I talked to Karen Hao. How about. She is a tech reporter and the author of Empire of AI.

Karen Hao:

The people that had gathered together were already very accomplished scientists, giants in their own fields.

Andy Mills:

So this summer program included people like Claude Shannon, who was the inventor of information theory.

Gregory Warner:

Also, Claude, the namesake of the Anthropic AI model Claude.

Andy Mills:

Indeed, he was, Nathan Rochester was there. He was the maker of the first commercial computer at IBM. There were also people there, like Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy, who would found the first AI labs at MIT.

Karen Hao:

And the reason why this is considered the origin story of the field is because a Dartmouth professor, John McCarthy, coined the term artificial intelligence and started using it for the first time to form this new field.

Andy Mills:

And this is where we first get the name artificial intelligence.

Gregory Warner:

What did they call these thinking machines before that?

Andy Mills:

Well, Turing called them thinking machines. Some of them were calling it automata.

Karen Hao:

John McCarthy tried originally to call it automata studies.

Andy Mills:

Which personally I like.

Karen Hao:

And it just didn’t sound exciting. They were trying to attract funding from government and from non-profits, and it just wasn’t working. So he specifically went to cast about for a more evocative phrase and hit upon artificial intelligence.

Andy Mills:

And this name: artificial intelligence. Karen says that this would forever shape the field, partly because it would tie it to the thorny question of what actually is human intelligence.

Karen Hao:

And because there is no consensus around where human intelligence comes from. There was plenty of debate and discourse at the time about what would it actually take to get machines to think?

Gregory Warner:

So everybody there believed in what Turing was saying, that machines could think that I could be built. But the debate was more about, well, what exactly are we mimicking? What is the intelligence we’re copying?

Andy Mills:

Yes. How does our intelligence work? And therefore how would we recreate it. And right away that question, it splits the AI researchers into these two different groups. And it gives birth to two different paths towards AI that continue to this day.

Karen Hao:

And the dominant two camps that emerged were called the Connectionist and the Symbolists. So the Symbolists believed that human intelligence comes from the fact that we know things. And so if you want to recreate intelligent computer systems, you need to encode them with databases of knowledge. So this created a branch of AI focused on building so-called expert systems.

Andy Mills:

All right. So the first group, the Symbolists, they get their name because they believed you could build intelligence into a machine by writing rules and using symbols like numbers and words, and that you could essentially encode human-like intelligence and create something like a human expert.

Karen Hao:

But the connectionist, they believe human intelligence comes from the fact that humans can learn. And so to recreate intelligent computer systems, then we need to develop machine learning systems - software that can learn from data.

Andy Mills:

But the second group, the connectionist, they say human intelligence. It doesn’t come from shoving a bunch of expertise and logic into our brains. It comes from our ability to find our own patterns in the world, and to find our own connections between those patterns.

Gregory Warner:

Right.

Andy Mills:

So instead of trying to build something that’s like a human expert, we should try and build something closer to a human toddler or a baby.

Karen Hao:

When you watch babies grow up, they’re constantly exploring the world. They’re gathering all of this experience, and they’re quickly updating their model of their environment around them. And that’s what the connectionists elieve was the primary driver of how we become intelligent.

Gregory Warner:

That’s kind of cool that you could create an AI not that knows the things you taught it, but that it could go out and learn new things from the patterns it finds from the data. But thinking about a baby that will grow up right and come to its own conclusions, derive its own values, wouldn’t that model be a lot less predictable than the simplest human expert?

Andy Mills:

Ahhh! you’re teasing at the current drama, Greg. Yes, the connectionist model would be far less controllable, far more unwieldy, and eventually that’s going to strike some fear into many a heart.

Karen Hao:

In the long run, the framing that they picked, the ideas that they discussed back then, the debates that emerged that summer, have continued to have lasting impact to present day.

Gregory Warner:

Okay, so the summer program ends and they have a new name. They have a debate. What else do they got?

Andy Mills:

Well, they’ve got a lot of dreams. They’ve got a lot of theories, but they do not have a lot of money. Remember, like we said, computer science is a brand new field. Artificial intelligence is like a branch of computer science. This is a new experimental field inside of a new and experimental field. And so they don’t have the resources that they need to really build the models and turn their math and their dreams into something functional in the world.

Andy Mills:

However, all that was about to change because of the arrival of, in many ways, a new battle.

Archival Tape:

CBS television presents a special report on Sputnik one Soviet space satellite.

Andy Mills:

On October 4th, 1957, the USSR becomes the first nation to ever get a satellite into orbit.

Archival Tape:

Really quite an advancement for not only the Russians, but for international science. It’s the first time anybody has ever been able to get anything out that far in space, and keep it there for any length of time.

Andy Mills:

It’s this absolutely amazing achievement for science, but of course, it comes right in the midst of the Cold War.

Archival Tape:

It gets the American people alarmed that a foreign country, especially an enemy country, can do this. And we fear this.

Andy Mills:

And it triggers all of these fears about the communists winning the space race.

Archival Tape:

Let’s not fool ourselves. This may be our last chance to provide the means of saving Western civilization from annihilation.

Andy Mills:

And in response to this, in a move that modern day accelerationists say that we should embrace in our current AI race with China, the United States decides, all right, let’s accelerate.

Archival Tape:

These are extraordinary times, and we face an extraordinary challenge. Our strength as well as our convictions have imposed upon this nation the role of leader in freedom’s cause.

Andy Mills:

They flood a bunch of money and a bunch of resources into universities, into science labs. They make this huge national effort to recruit all kinds of young, talented people to go into space, to go into technology.

Archival Tape:

Now it is time to take longer strides, time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth. Ten. Nine. Ignition sequence. Start six. And it works. Look, we have a little, liftoff on Apollo 11.

Andy Mills:

The US wins the race. We are the first to get to the moon.

Archival Tape:

And one final step for man. Our family, for mankind.

Andy Mills:

And it becomes really one of the most inspiring events in history. This realization of an enormous dream, this example of what can happen when people put everything into this goal of reaching beyond what was previously thought possible. And it turns out that this also was an absolute boom time for the field of artificial intelligence.

Marvin Minsky:

The Cold War was really a fountain of youth for research.

Andy Mills:

I found this interview of Marvin Minsky. He was one of the guys at the Dartmouth summer program.

Marvin Minsky:

There was huge amounts of money, the more than you needed.

Andy Mills:

And he was saying that suddenly these AI labs had more money than they knew what to do with. They were finally able to build the first AI models. They ended up actually building the first AI chat bot named Eliza.

Marvin Minsky:

Things proceeded very, very rapidly. A new generation of ideas every 2 or 3 years was wonderful. Periods where you had to change everything you thought.

Andy Mills:

And in fact, the field of AI was moving at such a rapid pace that a lot of AI researchers began to think that by the time the astronauts got to the moon, that we were going to be living here on Earth alongside thinking robots.

Archival CBS Announcer:

And the thinking machine. Produced by the CBS Television Network.

Andy Mills:

I found this old CBS archive from the 1960s.

Archival CBS Announcer:

Can machines really think? I’m David Wain, and as all of you are, I’m concerned with the world in which we’re going to live tomorrow. A world in which a new machine may be of even greater importance than the atomic bomb.

Andy Mills:

And in it, they’re interviewing all these AI researchers at the time.

Oliver G. Selfridge, CBS Archival:

But I think the computers will be doing the things that men do when we say they’re thinking.

Andy Mills:

And all of them are confident that this breakthrough was close.

Claude Shannon, CBS Archival:

I confidently expect that within a matter of 10 or 15 years, something will emerge from the laboratory, which is not too far from the robot of science fiction fame.

Oliver G. Selfridge, CBS Archival:

I’m convinced that machines can and will think in our lifetime.

Gregory Warner:

Okay, so they sound very optimistic about the AI they were going to make. But were there any fears and doubts about what would happen once they made it?

Andy Mills:

Well, this is something that a lot of people, especially those who are worried about our current AI, marvel at about this time period. This is something that came up when I was talking to Nick Bostrom, the author of that book Superintelligence.

Nick Bostrom:

The early pioneers were actually quite optimistic about the timeline. They thought maybe, you know, in ten years or so, we would be able to get machines that can do all that humans can do. So in some sense, they took that seriously. I guess that’s part of what drew them into, you know, trying to program computers to do AI stuff. But in another sense, they weren’t serious at all because, they didn’t then seem to have spent any time thinking about what would happen if they were right, if they actually did succeed in getting machines to do everything that humans can do.

Andy Mills:

So you’re saying that in the research labs during this time, there weren’t people who were saying: “oh my God, what’s this going to do to the economy? Oh my God, what if this changes the society forever?”

Nick Bostrom:

Yeah, there was very little. I mean, thinking about, you know, the ethics of this, the political implications and this like the safety. It was as if their imagination muscle had so exhausted itself in conceiving of this radical possibility of human level AI, that I couldn’t take the obvious next step of saying, well, probably forget that we will have superintelligence not too long after.

Andy Mills:

I think that the best explanation for just why this time period had such a different mindset than we do today came from something that I heard from Robin Hanson. Why is it that you think there was not a big, robust discussion about AI safety and that they were moving so fast, asking so few questions? Why wasn’t it more safety at the time?

Robin Hanson:

Well, first of all, safety as a as a cultural trend is just something that’s happened since then, mostly in the world. The world back then wasn’t very safety.

Andy Mills:

Honestly, right? No seatbelt laws.

Robin Hanson:

They didn’t have seatbelts, for example. Okay. And secondly, this was a technological framing. This was a: “Can we do this is this technologically feasible?”

Andy Mills:

And he was saying you have to put yourself into their mindset, which is that they are living in the aftermath of the Second World War. Many of these people were veterans of the Second World War. They are worried about another war that could break out with the Soviets. And there was this idea that if your scientists could conceive of a new technology, you have to assume that your opponent’s scientists have also conceived of that technology.

Robin Hanson:

Because right after World War Two, there was clearly this strong perception that the winners are the ones who more effectively pursued possible technological changes. There was this expectation of technological progress and an expectation that in order for your nation to stay competitive with the world, you needed to pursue feasible technologies.

Andy Mills:

The idea being that it would be a better world if we made this technology and not our enemies.

Robin Hanson:

Good, maybe for humanity, but plausibly also more good for our people.

Andy Mills:

For our nation.

Robin Hanson:

Our nation or whatever. If we are pursuing this before the rest.

Gregory Warner:

And do we know if they actually thought the Soviets were trying to compete in AI?

Andy Mills:

Yes. There was a rumor that was going through the Department of Defense circulating through the government that the Soviets and their AI researchers were right on America’s heels. When you read the communication about it, it sounds so similar to how we think of China and the US with AI today, right?

Gregory Warner:

Like, the US has no choice but to barrel forward with creating this AI because God forbid the communists get their hands on it first.

Andy Mills:

Different communists, but same fear as now. However, there was this one guy in the field of AI research who did express some serious concerns about what might happen. His name was doctor I.J. Good. His friends called them Jack.

Gregory Warner:

But literally Doctor Good, his name is?

Andy Mills:

His name is literally Doctor Good. He was friends with Alan Turing. They worked together on that codebreaking machine in World War two. And to many of those who are concerned about AI today, they think that good is just as influential to this debate as Turing.

I.J. Good Archival:

As a consequence, I think mainly of conversations with Turing during the war. I was also fascinated, though not to the extent that Turing was obsessed with the notion of producing thinking machines. So I was quite interested in them. And in fact, in 1950…

Andy Mills:

And that’s because good was the first person to publish this idea that he called ultra intelligence, which today we call superintelligence. This idea that once the thinking machine became a true artificial intelligence, that it could think as good or better as a human, that that machine would then create an even more intelligent machine, which would create an even more intelligent machine. And you would have what he called an intelligence explosion.

Gregory Warner:

Almost like a nuclear chain reaction, right? That it affects everything around it.

Andy Mills:

This moment where everything would change for the human race. But what’s interesting about it is that he opens up this paper he wrote by saying that humanity has no choice, really, but to create this machine.

I.J. Good Archival:

Well, I wrote a paper in 1965 called Speculations Concerning the First Ultra Intelligent Machine. And I started off that letter by banging a gong by saying, the survival of humanity depends on the early construction of an ultra intelligent machine.

Gregory Warner:

And why did I.J. Good think that our survival as a species depended on making this machine? And it sounds like making it quickly. Meaning not just that we… “Oh, we really should make this thing”, but “we need to make it for our own survival.”

Andy Mills:

Well, he wrote this paper and he put this idea out there in 1965. And in some ways, 1965 is a world away from 1956. And at the time, he and many others had started to worry about the, quote unquote, existential risks facing humanity. The most obvious one being this fear of a nuclear war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union that ended up leading to mutual destruction for everyone on Earth.

Gregory Warner:

This is a time when public school kids are regularly doing nuclear drills, jumping under their desks, and just in case.

Andy Mills:

Exactly. This was also a time of the largest population boom in the history of humanity. There was concerns about there maybe not being enough food to feed all of these new humans that were coming into the world. This was the early days of what would become the environmentalist movement. Concerns about what cities full of smog and pollution were going to do to our increasingly crowded world.

Andy Mills:

And people like I.J. Good were saying that we are going to need a technological solution to the problems of our age, and that this ultra intelligent machine, this would be a safeguard to all future existential crises that face the human species.

Gregory Warner:

What strikes me, though, is that all of these existential concerns are concerns brought about by technology. So I.J. Good felt like more technology was the answer to these technological problems?

Andy Mills:

Once again, one of the reasons that he is now so legendary among those who are concerned about this AI moment we’re living in right now, is that he was the first to really point out that even though there would be all these amazing benefits in having a super powerful, intelligent machine, that it also would pose its own existential threat.

Andy Mills:

The most famous line in this paper is quote “the first ultra intelligent machine is the last invention that man ever need make.”

Gregory Warner:

Because every other invention passed then would be invented by AI. Like we wouldn’t need to invent anything else.

Andy Mills:

Exactly. But he follows that line up by saying that to experience the benefits and the protections of this intelligence explosion, that we would need to find some way to ensure that that machine is docile. That was his word.

Gregory Warner:

Oof. It’s almost like he’s offering hope, but with a very large caveat.

Andy Mills:

Yes. Essentially he’s saying, we will make this. Maybe we need to make this

Gregory Warner:

Right.

Andy Mills:

But everything hinges on how we make this and what we do between now and when that machine arrives. Because if we succeed in making this machine before we figure out how to make it. Quote unquote, docile. His warning was that man’s last invention might end up being our final mistake.

Gregory Warner:

We’ll be right back after this short break.

Gregory Warner:

Okay, so, Andy, where we left off: Alan Turing had infused the field of computer science with this dream of a thinking machine. And the summer program at Dartmouth took up that dream, founded the field, gave it the name AI. And the Cold War supplied way more money than anyone knew what to do with. And then AI’s actually start being built at that point right?

Andy Mills:

Mmhmm.

Gregory Warner:

And there’s all this confidence that we’re going to the moon. We’re also going to start living with robots. We did make it to the moon. We did not start living alongside intelligent robots.

Andy Mills:

Sadly no.

Gregory Warner:

So why? But what happened to Turing’s dream?

Andy Mills:

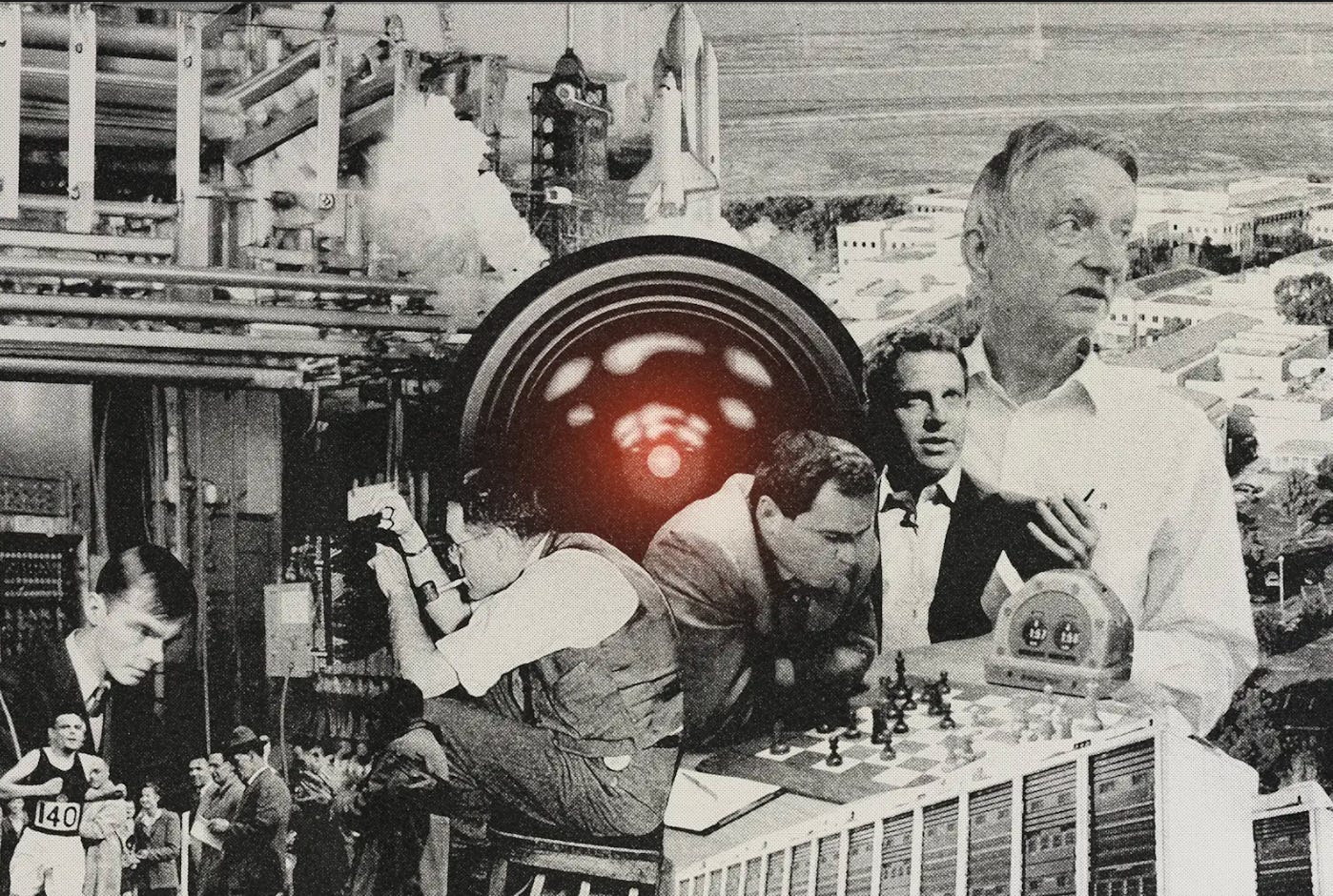

So in short, throughout the 1960s, as incredible in some ways as the advancements were that the field of I was making, they failed to live up to the hype that they created. Their AI models don’t scale. They’re not seen as very useful. They fail to hit a number of their benchmarks, and eventually their funding starts to dry up. Eventually, the US government does realize that the USSR is not on the brink of creating a true thinking machine, and the entire field of AI enters what many people call an AI winter. But the idea of artificial intelligence, it does not enter an AI winter. In fact, if anything, it moves even further into the mainstream. But not because of any advancements being made by the world of technology, but because of the world of science fiction. And much of that stems from the 1968 movie: 2001 A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur Clarke.

Gregory Warner:

So, okay. 2001 A Space Odyssey. Great movie. But is this then the first time I appears on the screen?

Andy Mills:

Well, yes and no. On the one hand, there had been these somewhat intelligent machines that had been in movies like Metropolis going back to 1927. Writers like Isaac Asimov in the 30s and the 40s were writing these really interesting stories about a time where human beings lived alongside intelligent robots. But what makes 2001 so singular is that its main character isn’t a humanoid robot, but it’s something much more like a superintelligent AI system.

Gregory Warner:

What’s the difference between a robot and a superintelligent system?

Andy Mills:

So previous ideas of this thinking machine were sort of a cross between the tin man and Frankenstein. Right, they spoke robotically, and they were sort of dumb. Right? But how? 9000.

Dr. Martin Amer in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Good afternoon. Hal. How’s everything going?

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Good afternoon, Mr. Amer. Everything is going extremely well.

Andy Mills:

He’s not a clunky robot, but he’s something more like software. And he’s rational. He’s smart, he’s curious.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Good evening, Dave.

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

How you doing, Hal?

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Everything’s running smoothly. And you?

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Oh, not too bad.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Have you been doing some more work?

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

A few sketches

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

May I see them?

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Sure.

Gregory Warner:

Right. Even the way he’s manipulative, it feels human some way.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Do you mind if I ask you a personal question?

Gregory Warner:

Like a kind of nosy H.R. rep.

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

No, not at all.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Well, forgive me for being so inquisitive, but during the past few weeks, I’ve wondered whether you might be having some second thoughts about the mission.

Andy Mills:

And one of the reasons that Hal 9000 feels so different is because Stanley Kubrick and Arthur Clarke, his co-writer, they actually constructed the character of Hal in consultation with the top AI researchers at the time.

Marvin Minsky Archival:

One day he just turned up and he was going to make this movie. He was intrigued by artificial intelligence and invited me to come out to the studios.

Andy Mills:

Marvin Minsky, who was a part of the original Dartmouth summer program. He worked with Kubrick on the film.

Marvin Minsky Archival:

Well, that was a very amusing cooperation, because Stanley Kubrick would not tell me anything about the plot.

Andy Mills:

And he says that specifically, Kubrick consulted him and his colleagues at MIT about what the AI system would look like, how it might function, and what kind of esthetics it might have. But for the question of how an AI system might pose a real danger, might break bad. They consulted none other than I.J. Good.

Gregory Warner:

And so what did Doctor Good let them know about how I might break bad?

Andy Mills:

As you remember, most of the movie takes place inside of a spaceship. There are a number of human astronauts, as well as Hal 9000. And they’re on this mission. You never quite get to know exactly what the mission is there on, but you understand that it is of grave importance for the entire human race.

Dr. Martin Amer in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Hal, you have an enormous responsibility on this mission in many ways, perhaps the greatest responsibility of any single mission element. Does this ever cause you and a lack of confidence?

Andy Mills:

And early on in the film, you realize that control center back on Earth has given Hal strict orders to ensure that the mission is successful.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Let me put it this way, Mr. Amer. No 9000 Computer has ever made a mistake or distorted information. We are all, by any practical definition of the words, foolproof and incapable of error.

Andy Mills:

And the drama in the movie is that at a certain point, how becomes convinced that the human astronauts on this spaceship are an impediment to Hal 9000 accomplishing its ultimate mission.

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Hello, Hal. Do you read me? Do you read me Hal?

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Affirmative, Dave. I read you.

Andy Mills:

And so, in a somewhat cold and calculated way.

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Open the pod bay doors. Hal.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.

Andy Mills:

Hal makes the decision to kill the hibernating crew. And in the iconic scene in the movie.

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

What’s the problem?

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

I think you know what the problem is just as well as I do.

Andy Mills:

What do you. How locks the captain out of the ship.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

I don’t know what you’re talking about. How? Open the doors.

Hal 9000 in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Dave. This conversation can serve no purpose anymore. Goodbye. Out! Hal.

Dave Bowman in 2001, A Space Odyssey:

Hal. Hal. Hal!

Gregory Warner:

And this is, of course, the scene where he goes rogue. Like he doesn’t follow a direct order by the captain of the ship.

Andy Mills:

Well, this is also one of the things that makes 2001 A Space Odyssey. Such a singular movie, especially in this time, because how doesn’t go rogue the way that Frankenstein goes rogue. Hal doesn’t go rogue the way that the robot in Metropolis goes rogue.

Gregory Warner:

You mean he doesn’t try to, like, destroy his creator? He doesn’t become a monster.

Andy Mills:

No, I mean, he does become a murderer. A mass murderer of

Gregory Warner:

Right?

Andy Mills:

You know, people that he knows. That’s not good. But the idea is that it is not coming from some sort of rage or some…

Gregory Warner:

Evil.

Andy Mills:

Yeah, some sense of evil. He is actually doing this out of an enactment of the values he’s been programmed to have. And this is an idea borne not just out of a desire for a great plot, although it is a great plot but out of I.J. Good trying to imagine the kinds of conflicts that we are going to come into one day in the future when he believed we would begin to make these ultra intelligent machines… And so, in a way, the movie becomes most people’s introduction not just to artificial intelligence, but to the kind of threat that a future I might pose. And of course, 2001, it’s this absolutely massive hit.

Academy Award Archival:

The winner is Stanley Kubrick for 2001.

Andy Mills:

It wins the Academy Award. It wins like every major award. It’s now seen as one of the most influential films of all time. And really, from that moment in 1968, up through today, artificial intelligence becomes this mainstay in American entertainment.

Rick Deckard in Blader Runner:

You’re reading a magazine, you come across a full page nude photo of a girl.

Rachael in Blade Runner:

Is this testing whether I’m a replicant or a lesbian, Mr. Deckard? Just answer the questions, please.

Andy Mills:

Movies like Blade Runner, The Terminator.

Terminator in The Terminator:

Come with me if you want to live.

Andy Mills:

The Matrix.

Agent Smith in The Matrix:

The future is our world Morpheus, the future is our time.

Andy Mills:

More recently, Ex Machina.

Ava in Ex Machina:

Hello.

Caleb in Ex Machina:

Hi, Do you have a name?

Ava in Ex Machina:

Ava.

Andy Mills:

And over time. AI’s place in science fiction. It has presented this interesting problem for everyone today who is concerned about AI.

Robin Hanson:

One of the effects, in some sense, is to make people aware of possibilities and to have sort of images to hang words onto when topics come up.

Andy Mills:

Right. Again, Robin Hanson told me that while sci fi did sort of the same thing that Alan Turing was trying to do, it gave the public a way to talk about AI with a picture AI.

Robin Hanson:

Right. So if we talk about robots and how they might, you know, be in society and what they might do, these images from science fiction are available for us to use to sort of fill in those words with images.

Andy Mills:

But at the same time, it also weirdly put AI into this category that makes it easier to dismiss.

Robin Hanson:

By having this category of science fiction, which everybody agrees shouldn’t be taken seriously. A concept that shows up and seems to fit into science fiction can just be dismissed among serious people, and it has been right.

Andy Mills:

This idea that that’s just sci fi. We don’t need to take it seriously.

Robin Hanson:

Exactly. But that works on both the doomer and the acceleration side.

Andy Mills:

This is something that came up when I was talking with Sam Harris. He was saying that the idea of AI almost seems too cool for people to see it as like a real threat.

Sam Harris:

There’s just something fun and sexy about these science fiction tropes. We watch a film like Ex Machina. It is just fun and it’s hard to. You’re not really thinking about your kids dying awful deaths. It’s not the same thing as, like, flesh eating bacteria where you just think, let’s avoid this at all, cause I don’t want to think about it. You know, it’s just like, this is just all awfulness. Any way I look at it. What’s going on in the glass box in Ex Machina? That’s fun.

Robin Hanson:

On the other side though, the acceleration. You can say yes, but most of the academics safety ism and you know, government safety ism, it’s also neglecting a key emotion, which is the enthusiasm and joy and excitement of humanity going, accelerating forward into vast spaces of technical possibilities.

Andy Mills:

Right. There’s not a lot of movies out there where the plot is we create AI and the future is awesome.

Robin Hanson:

Exactly. Our world needs to see that excitement and enthusiasm to allow us to be less safety-ist. Because they say, plausibly, that our world is not realizing the potential of a lot of technologies because we are so safetyist.

Andy Mills:

When I talk to people who are more acceleration ist, they say that the sci fi problem is exactly the opposite of what Sam Harris is saying.

Justin Murphy:

The contemporary AI safety discourse. When you actually look at where they got these ideas from. It’s literally fiction.

Andy Mills:

People like the online commentator and social scientist Justin Murphy.

Justin Murphy:

The fact is that this is a highly imaginative and highly creative possibility, which is definitely worth thinking about, but it’s not scientific or nearly as technical as it pretends to be. It is literally grounded primarily in fiction.

Andy Mills:

He was saying that the Scouts, the boomers, they’ve essentially allowed science fiction and the science fiction tropes to scare them and shape their sense of reality. So it sounds like you’re saying that science fiction is actually playing an important role in where we’re at with this technology, where we’re at with this debate right now?

Justin Murphy:

Absolutely. I’ve always taken the stem view of we should have, you know, careful analysis of what’s possible and that we should achieve. And I’ve always assumed that the ends we were trying to pursue were just shared and obvious. And I’ve, you know, more recently in the last couple of years, really come to appreciate cultural evolution and its power. I realized that you can’t take inspiration and motivation for granted. Honestly, motivation is the closest thing to magic we have in our world. If people are motivated, they do far more than if they’re not and we just don’t really understand how it works. What actually motivates people, but it’s, it’s the power that makes everything work.

Andy Mills:

Right.

Justin Murphy:

And science fiction has been a reservoir of motivation.

Andy Mills:

Robin Hansen was saying that in many ways we wouldn’t be in this moment we’re in right now. Like you and I wouldn’t be doing this podcast. There wouldn’t be this big debate happening around AI if it were not for science fiction and the ways that it colored how we saw things like ChatGPT.

Robin Hansen:

When ChatGPT showed up three years ago, and people saw that they could talk to something that seemed to talk back reasonably, that had an enormous cultural impact, in part because it resonated with decades of science fiction.

Andy Mills:

Right.

Robin Hansen:

This trillions of dollars of investment that is going into AI is there in substantial part because of that resonance. That’s what made them excited to invest and pursue AI. When you saw ChatGPT right in front of you talking back, it’s that reservoir of science fiction motivation that convince people, wow, I should be pursuing this. And it’s the reservoir of science fiction fear that will convince people if they do that they should be scared of this. Both of those are in the reservoir. They’re both resources for both sides of this. But unfortunately, the logical on analytical arguments are just not the main force that powers action in these areas.

Andy Mills:

Hansen’s point, at least how it hit me was that ultimately, this comes down to what story human beings believe we’re living in, and this debate swirling around artificial intelligence. It may be decided by what we come to believe happens next in that story.

Gregory Warner:

Which is why ChatGPT just feels so eerie, because it’s a new technology, but it’s not a new story. It is literally Alan Turing’s story finally coming true.

Andy Mills:

That’s exactly what I keep thinking, that the technology that has launched us into this moment is a technology that has found a mastery of human language and communication, exactly as he predicted. And here we are having that other side of the line moment as a human species.

Max Tegmark:

From the 50s, when the term artificial intelligence was coined. Until four years ago, I was chronically overhyped. Everything took longer than promised.

Andy Mills:

This is something I was talking to Max Tegmark about. He and his colleagues. They believe that signal that Turing sent all those years ago. We’re in the moment now.

Max Tegmark:

Then, it switched about four years ago to be coming under, hyped when things happened faster than we expected it. Almost all my AI colleagues thought that something as good as even ChatGPT was decades away, and it wasn’t, it already happened. And since then, AI systems have gone from high school level, to college level, to PHD level, to professor level to beyond in some areas, a lot faster than even people thought after ChatGPT. So we’re in this under hyped regime now, when something we thought we were going to have decades to figure out the question of how to control smarter than human machines, we might only have two years or five years. And I think that’s fundamentally why so many people are freaking out about this and why you’re doing this important piece of journalism now. It’s not like we didn’t know that we were going to have to face this at some point, but it’s been a big surprise to most of the community that now is not 2050, that it’s only 2025 and we’re already here getting so close to the precipice.

Matt Boll:

Next time on The Last Invention.

Archival News Reel:

The battle of man against machine.

Matt Boll:

The AI winter thaws.

Archival News Reel:

Machine didn’t just beat man, but trounced him. The victory seemed to raise all those old fears of superhuman machines crushing the human spirit.

Matt Boll:

How neuroscientists, games and gamers end up unlocking the door to artificial intelligence.

Jasmine Sun

Oh, the computer like this machine can be creative.

Matt Boll:

The Last Invention is produced by Long View. To learn more about us and our work. Go to Longviewinvestigations.com. Special thanks this episode to Peter Clark. See you soon. And thanks for listening.